The Greystones family home of Fred Heuston and his twin brother Frank was St David’s – a substantial Victorian house on Marine Road.

Long after the Heustons lived there, it was bought by the Holy Faith Sisters in 1941 and helped pave the way for the school that today bears its name.

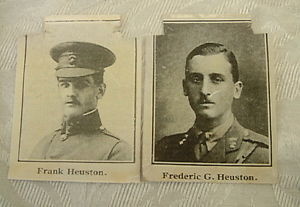

The Heustons – father Dr Francis Thomas Heuston and mother Frances Letitia Heuston – had three children: a daughter named Frances Elizabeth, who worked at the Adelaide Hospital, then in Peter Street in the centre of Dublin, and twin boys – Robert Francis, known as Frank; and Frederick Gibson, known as Fred.

The Heustons also had a home in the city. It was No 15 St Stephen’s Green – the house that is now home to the Little Museum of Dublin, which is well worth a visit.

The head of the Heuston household was a significant figure in Irish medical circles.

He was Professor of Anatomy at the Royal College of Surgeons just across the Green from No 15. He was also Senior Surgeon at the Adelaide, of which he was also secretary and chairman, Consulting Surgeon at the Coombe, and he was connected to the Cripples’ Home in Bray and the Children’s Home in Delgany, as well as being President of the Carmichael College of Medicine and a regular contributor to medical journals.

Photo: Heuston bros

The twins both went to St Columba’s College in Rathfarnham and when war came, Fred beat his brother Frank, signing up three days before he did. Fred applied to join the infantry and, after being declared fit and healthy following an examination at Portobello Barracks, he was assigned to the 6th Battalion of the Royal Irish Fusiliers.

Fred was among those soldiers who landed at Suvla Bay on the night of August 6th/7th and he survived until August 15th – all of nine days. No record survives of his actions during those days but he clearly impressed his superior officers for he was awarded a Military Cross.

The Cross, one of the higher honours than can be bestowed on a British soldier, was created in December 1914 and given for “an act or acts of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy”.

There is no citation for the award of the Cross to Fred and it cannot be awarded after death. However, it was common practice at the time for senior officers to award one to a soldier who had just been killed, citing the soldier’s general conduct beforehand as exemplary of the bravery and determination they hope to see from the men generally.

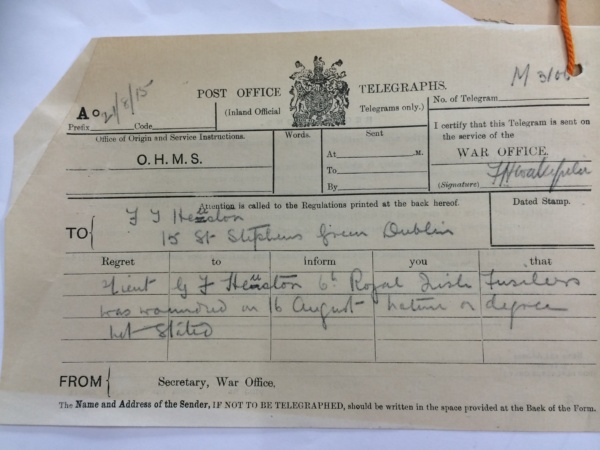

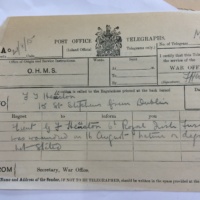

It was some time before the grim news about Fred was relayed home.

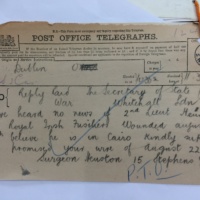

On August 21st, Dr Heuston got a telegram whose alarm can only have been heightened by the paucity of information.

Photo: Heuston FG telegram

“Lieutenant G F Heuston, 6th Royal Irish Fusiliers, was wounded on 16 August – nature or degree not stated”.

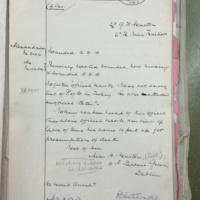

Inside Fred’s military service file, there follows an exchange of telegrams and letters between the War Office and his family that reflect what must have been a period of sheer torture for his parents and sister here in Ireland.

Photos: Heuston father letter 1 (left) and Heuston father letter 2 (right)

Dr Heuston replied to the telegram the following day, writing as a father and doctor. “I would be much obliged by your letting me know at your earliest convenience the nature and position of the wound and whether it is of a serious character or not, also to which hospital he has been sent.”

Photo: Heuston FG father plea

On August 25th, he again telegrammed the War Office, this time from Greystones, asking to which hospital Fred had been taken? “Kindly say is he at Alexandria or Malta?” he pleaded, signing himself Surgeon Heuston, Greystones.

But still no information came back. . .

On September 3rd, he sent another telegram from Greystones, telling the War Office that he was still waiting for a reply. “I have received no information as to where he is or nature of wound which I await anxiously”, he wrote, signing himself again as Surgeon Heuston, Greystones.

Dr Heuston appears to have had sources of his own, perhaps through his medical network, for on September 15th, he again telegrammed the War Office stating “believe he is in Cairo – kindly supplement, as promised, your wire of August 22nd”.

In October, the War Office replied, stating that Fred was now regarded as “missing and wounded”.

Photo: Heuston father old

Dr Heuston never got to find out what happened to his son – for he himself died on November 26th aged just 58.

A short report in the following day’s Irish Times reads as though he had a heart attack – he died just after midnight, it said, in his Stephen’s Green home.

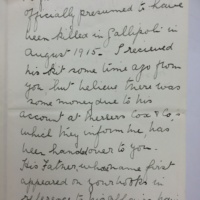

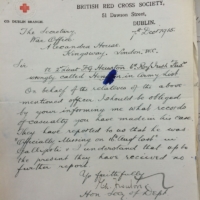

The search for information about Fred was taken up by his sister, Frances.

Photos: Heuston daughter letter 1 (left) and Heuston daughter letter 2 (right), side by side

Writing on December 3rd, she asked the War Office to deal henceforth with her, as “my father died last week and my only brother is serving in France”.

“Any information, official or otherwise, would be gratefully received,” she wrote. “According to rumours received here, some of his company stretcher bearers state that they found him dead from an abdominal wound”.

A War Office internal note states that a reply was sent to Frances telling her there was no further information.

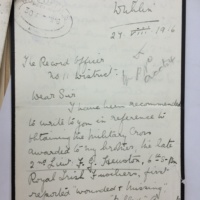

Photo: Heuston FG red cross letter

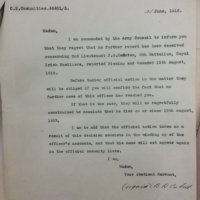

The family turned for help to the Red Cross. The War Office replied twice to their inquiries that Fred remained classified officially as “wounded and missing” and that the family had been told as much.

No one ever did find 2nd Lieutenant Frederick Gibson Heuston. His body was either returned to the earth through nature’s own means or was interred at Gallipoli – one of the many thousands that lie in one of Suvla’s many cemeteries, known only unto God but remembered on the Helles Memorial on the bluff above Sedd-ul-Bar.

For his mother, receipt of his Military Cross assumed an understandably larger importance.

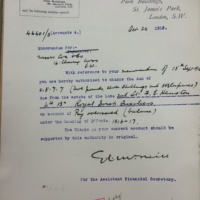

Photo: Heuston military cross letter 1

In December 1916, she wrote to the War Office seeking a public awarding of the medal.

All that there is in Fred’s file is a note to the effect that the Cross had been forwarded to GHQ Home Forces in January 1917 for a public presentation.

Photo: Heuston military cross file record 2 (zoom into text pls)

I have been unable to find out whether it was, indeed, ever formally presented in public, a validation for Mrs Heuston that her son had died for something.

**

Photo: Heuston Frank

Frank Heuston seems to have been something of a character, notwithstanding his conventional upbringing which included prep school in England and, like Fred, attending St Columba’s College.

In 1912 aged 19, he went off to Nova Scotia in Canada, characterising himself as an engineer. He had his left forearm tattooed – a rising sun with the inscription in Latin ora et labora – pray and labour – a motto sometimes ascribed to St Benedict.

In January 1914, he enrolled in the Nova Scotia-based Princess Louise Fusiliers, a light infantry that during the war, serviced as a conduit for locally recruited soldiers into battalions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Photo: Heuston Frank Valcartier training camp

Frank became a Lieutenant in 1st Royal Montreal Regiment. He was inducted at Valcartier military training camp near Quebec City, which was created hastily in August as part of the general mobilisation in Canada. He was promoted to Captain in August 1915, the month of Fred’s death in Gallipoli.

But Frank was posted not to Turkey but to France, sailing to England from Canada on board the RMS Andania on October 4th, bound for a period of training on the Sailsbury Plain. By November 1916, he was in France, fighting on the Western Front, a stint at war relieved in December when he was allowed home to Dublin on compassionate extended leave following the deaths of Fred and also his father.

He was eased back into combat in early 1916 with a short stint at a military school and in February, while apparently off duty and, as a colleague noted, “sky larking with another officer in his billet”, he hurt his foot by jumping through an open window, landing on broken glass, cutting himself and damaging a bone in his foot.

By April, he was back on the front line in the hotly contested area north-west of Arras and centered around the village of St Eloi.

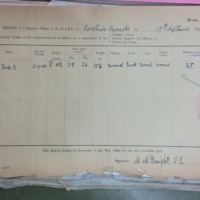

Photo: Heuston Frank war diary (suggest zoom in on yellow highlighted bits)

The War Diary intelligence summary of the 14th Canadian Battalion relates the events of the first week of the month: “heavy artillery duel. . .heavy guns very active. . .headquarters shelled spasmodically. . .great rifle grenade activity on both sides. . .bombers bombard enemy heavily with rifle grenades. . . Lieutenant F R Heuston killed”.

Photo: Heuston Frank death report

The report of his death contained in the Canadian archives is a little more detailed, even if the year in the date is incorrect: “When in the trenches near Ypres observing the effect of Rifle Grenades which the bombers were firing into the German trenches at about 5.00 o’clock on the afternoon of April 6th 1917 – it was in fact 1916 – he was shot in the head by a sniper’s bullet, which rendered him unconscious. He was removed to No 10 Casualty Clearing Station where he succumbed to his wounds at about 10.15 o’clock the following morning without regaining consciousness.”

Photo: Heuston Frank

Photo: Heuston Frank

Like Fred, Frank Heuston was just 22 years old.

He is buried in Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery.

Within a nine month period, from August 1915 to April 1916, Mrs Heuston had lost her husband and her twin boys. Her daughter Frances had lost her father and her brothers.

By the end of April, mother and daughter were selling their Stephen’s Green home and moving permanently to St David’s in Greystones. In due course, Mrs Heuston went to live on South Novington Farm, in Plumpton near Lewes in Sussex.

Like her late brother Frank, Frances went to Canada, to Vancouver where she married a lawyer, Ghent Davis, heir to a substantial legal firm in the city.

Photo: Heuston Canada home

She and Ghent were very well off, as evidenced by this, the Vancouver home in which they lived which Ghent’s father had built overlooking the sea. It is now part of the University of British Columbia and is used for social and college events.

Ghent Davis had a brother. His name was Irwin and, just like Fred and Frank, he enlisted for the war and, just like Fred and Frank, he was killed.

Photo: Heuston Frances with her baby boys

When Ghent and Frances had a baby boy, to whom Frances gave birth in Lewes Sussex incidently, they named him Irwin. He’s on the left in this photo. And when they had a second boy, on the right, they named him Fred – surely after Frances’s lost brother.

Irwin Davis grew to be a very well-known figure in Vancouver – familiar in the city’s legal, property and arts worlds and a man renowned for his old world charm, grace and manners.

He fought in the second World War and later worked in his father and grandfather’s law firm. He died in 2008 after a long and happy life with Robert, his partner for 45 years.

Photo: Heuston mother and daughter (leave on screen during music); come

Frances was a beautiful young woman and she retained her radiance in old age.

Beside this photograph of her is her mother, Frances Letitia Heuston of St David’s on Marine Road in Greystones, a portrait that hangs on the wall of Robert’s apartment in Vancouver.

It shows a young woman ready for society — but not, surely, for the tragedy that would take from her, her yet-to-be-born twin boys, Frank and Fred.